By Jeffrey L. Littlejohn, Sam Houston State University and Zachary Montz, Sam Houston State University

The news was startling.On June 19, 1865, two months after the U.S. Civil War ended, Union Gen. Gordon Granger walked onto the balcony at Ashton Villa in Galveston, Texas, and announced to the people of the state that “all slaves are free.”

As local plantation owners lamented the loss of their most valuable property, Black Texans celebrated Granger’s Juneteenth announcement with singing, dancing and feasting. The 182,566 enslaved African Americans in Texas had finally won their freedom.

One of them was Joshua Houston.

He had long served as the enslaved servant of Gen. Sam Houston, the most well-known military and political leader in Texas.

Joshua Houston lived about 120 miles north of Galveston when he learned of Granger’s proclamation.

It was read aloud at the local Methodist Church in Huntsville, Texas, by Union Gen. Edgar M. Gregory, the assistant commissioner for the Freedmen’s Bureau in Texas.

If Juneteenth meant anything, it meant at least that Joshua Houston and his family were free.

But there was more too.

The promise of freedom meant that more work needed to be done. Families needed to be reunited. Land needed to be secured. Children needed to be educated.

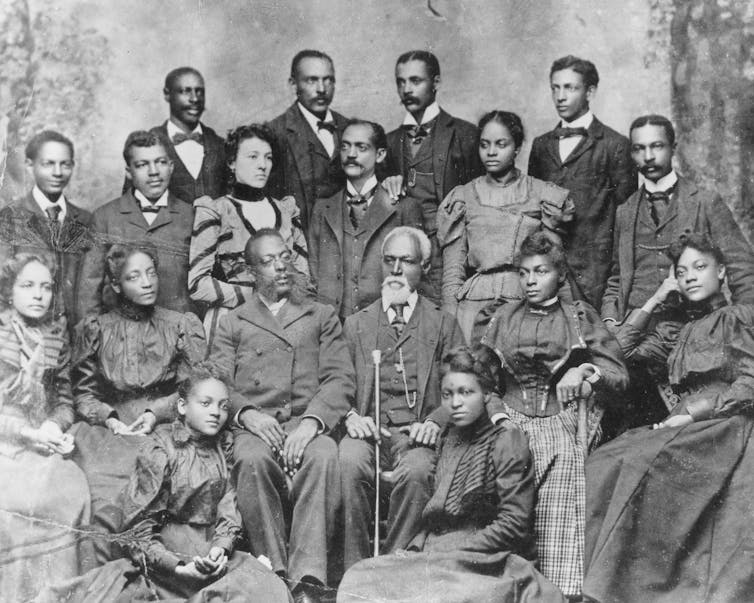

Indeed, the radical promise of Juneteenth is embodied in the community activism of Joshua Houston and the educational career of his son Samuel Walker Houston.

The violent white reaction to Black political power

Within a year of Granger’s proclamation, Houston had established a blacksmith shop near the Huntsville town square and moved his family into a two-story house on the adjoining lot.

He helped found the Union Church, the first Black-owned institution in the city, as well as a freedmen’s school to begin educating African American children.

In 1878 and 1882, a Republican coalition of Black and white voters opposed to conservative Democratic rule elected Houston as the county’s first Black county commissioner, a powerful position in local governance.

Despite this dramatic turn of events, Houston’s political story was hardly unique.

In the two decades following emancipation, 52 Black men served in the state Legislature or the state’s constitutional conventions.

But that number had fallen to two by 1882.

Opposition to Black freedom had been a powerful force in the state’s political culture since emancipation.

Armstead Barrett, a former slave in Huntsville, recalled in 1937 that an enraged white man had reacted to Granger’s Juneteenth order by riding past a celebrating Black woman and murdering her with his sword.

In 1871, the violence continued when the white citizens of Huntsville stormed the county courthouse and aided the escape of three men who had lynched freedman Sam Jenkins.

Later, in the 1880s, attacks on Black elected officials, their white political allies and Black voters escalated dramatically.

In the early 1900s, changes in state election laws, including the introduction of the poll tax, effectively disenfranchised most Black voters and many poor whites as well. Voter participation dropped from roughly 85% at the high tide of Texas populism in 1896 to roughly 35% when the poll tax became effective in 1904.

As a result, Robert Lloyd Smith was the last Black legislator for nearly 70 years when he finished his term in 1897.

That wall of white supremacy at the state Capitol would not crack again until 1966, when federal voting rights legislation and Supreme Court rulings nullified schemes to deny African Americans the ballot.

These changes enabled the election of Black officials such as Barbara Jordan, the first African American woman to serve in the Texas Senate.

Like father, like son

On an unknown date, a few years after Juneteenth, Joshua Houston’s son Samuel Walker Houston was born free in the bright light of Reconstruction.

Although he spent his adulthood in some of the darkest years of Jim Crow, he continued his father’s work as an educator and community leader. Following a short stint at Atlanta University in Georgia and Howard University in Washington, D.C., Samuel Walker Houston returned to Huntsville and founded a school in the nearby Galilee community.

Houston’s school was named for him and served as one of the first county training schools for African Americans in Texas. It enrolled students at every level, from first grade through high school, and provided a curriculum based on Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee model of vocational training.

Young women at Houston’s school received training in homemaking, sewing and cooking, while young men learned carpentry, woodworking and mathematics.

By 1922, enrollment at the school had grown to 400 students, and it was recognized by contemporaries as the leading school of East Texas. In the 1930s, Houston’s school was absorbed into Huntsville’s school district, and he became the director of Black education in the county.

Houston encouraged a practical education for Black Texans, but he also believed that young Texans of all races needed to learn an account of history that differed from the white supremacist narrative that dominated Southern history.

Toward this end, he joined with Joseph Clark and Ramsey Woods, two white professors who pioneered race relations courses at Sam Houston State Teachers College. Together, the group led the Texas Commission on Interracial Cooperation’s effort to evaluate Texas public school textbooks during the 1930s.

In an analysis of racial attitudes in state-endorsed textbooks, they found that 74% of books presented a racist view of the past and of Black Americans. Most excluded the scientific, literary and civic contributions of Black people, while mentioning their economic contributions only in the period of slavery before the Civil War.

Instead, the group argued, books designed for both Black and white Texans needed to take the “opportunity … to do simple justice” by including Black history and the “struggle for the exercise” of equal civil, political and legal rights.

White Texans refused to adopt a textbook in the 1930s that taught the fundamental equality of the races, or portrayed Reconstruction, as it is now widely understood, as a missed opportunity to establish a more just and egalitarian Texas.

But Houston and his white counterparts were motivated by the conviction that progress, both for African Americans and for Texas, required a more honest and progressive account of the state and its history.

An ongoing battle for equality

Today’s legislative efforts in Texas and elsewhere to restrict the teaching of systemic racism in public schools ignore the lessons and realities represented by Joshua and Samuel Walker Houston’s lives.

The argument used for supporting such restrictions is that “divisive concepts” like the history of racism may make some students feel uncomfortable or guilty.

That sort of thinking echoes the same justification provided by Texas lawmakers in 1873, when many argued that the state’s schools must be segregated to ensure “the peace, harmony and success of the schools and the good of the whole.”

But the opposite is true.

In reality, the prohibition on teaching the darker chapters of our past creates a segregated history.

Instead, as Samuel Walker Houston recognized, young Texans must have a more honest account of the past and of one another to progress into a unified and egalitarian society.

Texas history is both the story of people who dedicated their lives to the work of advancing freedom and the story of powerful people and forces that stood against it.

One cannot be understood without the other.

Americans cannot appreciate the accomplishments of Joshua and Samuel Walker Houston without examining the vicious realities of Jim Crow society.

The lesson of their lives, and of the Juneteenth holiday, is that freedom is a precious thing that requires constant work to make real.![]()

Jeffrey L. Littlejohn, Professor of History, Sam Houston State University and Zachary Montz, Lecturer, History Department, Sam Houston State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)