Abortion has been common in the US since the 18th century – and debate over it started soon after

State-by-state battles are heating up in the wake of news that the U.S. Supreme Court appears poised to overrule landmark rulings - Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey - and remove constitutional protection for the right to get an abortion.

Now, pro- and anti-abortion advocates are gearing up for a new phase of the abortion conflict.

While many people may think that the political arguments over abortion now are fresh and new, scholars of women’s, medical and legal history note that this debate has a long history in the U.S.

It began more than a century before Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that established that the Constitution protects a person’s right to an abortion.

The era of ‘The Pill’

On Nov. 14, 1972, a controversial two-part episode of the groundbreaking television show, “Maude” aired.

Titled “Maude’s Dilemma,” the episodes chronicled the decision by the main character to have an abortion.

Roe v. Wade was issued two months after these episodes. The ruling affirmed the right to have an abortion during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. “Maude’s Dilemma” brought the battle over abortion from the streets and courthouses to primetime television.

Responses to the episodes ranged from celebration to fury, which mirrored contemporary attitudes about abortion.

Less than 10 years before “Maude’s Dilemma” aired, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first commercially produced birth control pill, Enovid-10.

Although various forms of birth control predate the birth control pill, the FDA’s approval of Enovid-10 was a watershed in the national debate around family planning and reproductive choice.

Commonly known as “The Pill,” the wider accessibility of birth control is seen as an early victory of the nascent women’s liberation movement.

Abortion also emerged as a prominent issue within this burgeoning movement. For many feminist activists of the 1960s and 1970s, women’s right to control their own reproductive lives became inextricable from the larger platform of gender equality.

From unregulated to criminalized

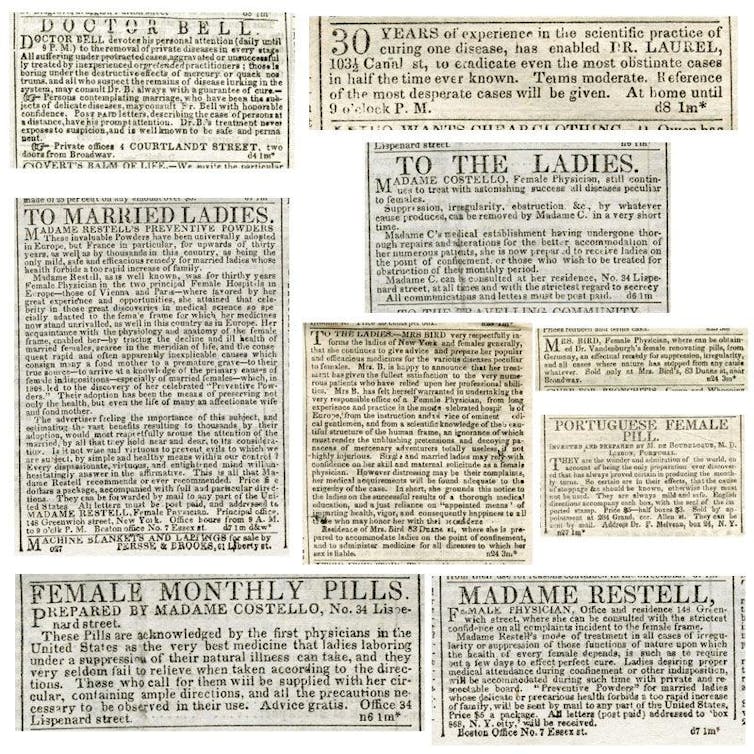

From the nation’s founding through the early 1800s, pre-quickening abortions – that is, abortions before a pregnant person feels fetal movement – were fairly common and even advertised.

Women from various backgrounds sought to end unwanted pregnancies before and during this period both in the U.S. and across the world. For example, enslaved black women in the U.S. developed abortifacients – drugs that induce abortions – and abortion practices as means to stop pregnancies after rapes by, and coerced sexual encounters with, white male slave owners.

In the mid- to late-1800s, an increasing number of states passed anti-abortion laws sparked by both moral and safety concerns. Primarily motivated by fears about high risks for injury or death, medical practitioners in particular led the charge for anti-abortion laws during this era.

By 1860, the American Medical Association sought to end legal abortion. The Comstock Law of 1873 criminalized attaining, producing or publishing information about contraception, sexually transmitted infections and diseases, and how to procure an abortion.

A spike in fears about new immigrants and newly emancipated black people reproducing at higher rates than the white population also prompted more opposition to legal abortion.

There’s an ongoing dispute about whether famous women’s activists of the 1800s such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony opposed abortion.

The anti-abortion movement references statements made by Anthony that appear to denounce abortion. Abortion rights advocates reject this understanding of Stanton, Anthony and other early American women’s rights activists’ views on abortion. They assert that statements about infanticide and motherhood have been misrepresented and inaccurately attributed to these activists.

These differing historical interpretations offer two distinct framings for both historical and contemporary abortion and anti-abortion activism.

Abortion in the sixties

|

| Photo credit: SHYCITY nikon |

By the turn of the 20th century, every state classified abortion as a felony, with some states including limited exceptions for medical emergencies and cases of rape and incest.

Despite the criminalization, by the 1930s, physicians performed almost a million abortions every year. This figure doesn’t account for abortions performed by non-medical practitioners or through undocumented channels and methods.

Nevertheless, abortion didn’t become a hotly contested political issue until the women’s liberation movement and the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. These movements brought renewed interest in public discussions about reproductive rights, family planning and access to legal and safe abortion services.

In 1962, the story of Sherri Finkbine, the local Phoenix, Arizona host of the children’s program, “Romper Room,” became national news.

Finkbine had four children, and had taken a drug, thalidomide, before she realized she was pregnant with her fifth child. Worried that the drug could cause severe birth defects, she tried to get an abortion in her home state, Arizona, but could not. She then traveled to Sweden for a legal abortion. Finkbine’s story is credited with helping to shift public opinion on abortion and was central to a growing, national call for abortion reform laws.

Two years after Finkbine’s story made headlines, the death of Gerri Santoro, a woman who died seeking an illegal abortion in Connecticut, ignited a renewed fervor among those seeking to legalize abortion.

Santoro’s death, along with many other reported deaths and injuries also sparked the founding of underground networks such as The Jane Collective to offer abortion services to those seeking to end pregnancies.

Expanding legal abortion

In 1967, Colorado became the first state to legalize abortion in cases of rape, incest, or if the pregnancy would cause permanent physical disability to the birth parent.

By the time “Maude’s Dilemma” aired, abortion was legal under specific circumstances in 20 states. A rapid growth in the number of pro- and anti-abortion organizations occurred in the 1960s and 1970s.

On Jan. 22, 1973, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Roe v. Wade nullified existing state laws that banned abortions and provided guidelines for abortion availability based upon trimesters and fetal viability. The subsequent 1992 ruling known as Casey reaffirmed Roe, while also allowing states to impose certain limits on the right to abortion. Roe remains the most important legal statute for abortion access in modern U.S. history.

Since Roe, the legal battle over abortion has raged, focused on the Supreme Court. If the draft opinion overruling Roe and Casey stands, the battle will end there and shift to the states, which will have the power to ban abortion without fear of running afoul of the Supreme Court. And the long history of conflict over abortion in the U.S. suggests that this will not be the last chapter in the political struggle over legal abortion.

This story is an updated version of an article published on June 10, 2019.![]()

Treva B. Lindsey, Professor of Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies, The Ohio State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

%20(4).png)