Wednesday, July 24, 2024

BROOKS BLACKBOARD

Thursday, September 7, 2023

61 “Stop Cop City” activists hit with racketeering charges

Atlanta organizers allege that this is the latest installment in the ongoing state repression against the movement to stop “Cop City” from being built

Atlanta residents have been fighting the proposed construction of a massive police training facility to be built on part of the region’s largest urban forests since 2021. Protesters allege that the training facility, dubbed “Cop City”, would hone the repressive tactics of the US police force and that it would contribute to increased repression against social movements, Black and Brown communities, and the working class as a whole. A mass movement has emerged in the city utilizing a diverse array of tactics including marches, forest occupations, direct action, and arts and culture.

The Atlanta Police Foundation and the state apparatus of Georgia have been attempting to subdue this movement every step of the way. The defendant list itself is a record of months of legal repression against the Stop Cop City movement. 42 out of the 61 defendants were previously charged with domestic terrorism. Defendants also include three activists who were charged with money laundering as a result of running a bail fund for arrested activists, a legal observer who was put in jail for monitoring protests, and three activists who were arrested for handing out flyers with the name of a police officer connected to the police killing of fellow protester Tortuguita.

“These charges are yet another flimsy and desperate attempt by the state government to crush the movement against police terror in Atlanta,” Stop Cop City activist Mariah Parker told Peoples Dispatch. “It shows that they have learned nothing in the course of this struggle: each time they have tried to snuff us out, we have emerged stronger and more organized. This will be no different.”

While the charges were filed last week, the date listed on all indictments is May 25, 2020. This was the day that unarmed Black man George Floyd was murdered in broad daylight by police officer Derek Chauvin, a killing that ignited a summer of the largest anti-police brutality protests in the United States to date. Prosecutors are tracing the actions of anti-Cop City protesters, who they label as “militant anarchists,” to the 2020 anti-racist protests—despite the fact that the Stop Cop City movement began in 2021.

As the Atlanta Community Press Collective reported, “In previous bond hearings for Stop Cop City defendants, prosecutors with the Georgia Attorney General’s Office have tried to link the George Floyd Uprisings to the Stop Cop City movement.”

“The Cop City RICO indictments allege the date when George Floyd was murdered by the police as the start of the ‘racketeering enterprise,’” wrote Atlanta-based activist and founder of Community Movement Builders Kamau Franklin. “The day a movement to abolish the police took on new life is the day for them a criminal enterprise was born.”

“This is a further attempt to criminalize a movement against police violence,” Franklin told Peoples Dispatch. “There is no basis in law to bring these charges. It is simply a scare tactic by the State and city against organizers.”

“It’s very clear that all levels of government in Georgia are committed to the same project that birthed the cop city proposal—absolutely stamping out any sort of radical movement against police brutality and this racist system,” Monica Johnson, Stop Cop City activist and anti-police brutality organizer told Peoples Dispatch. “This repression is part of the legacy of COINTELPRO, of trying to sever the ties between the community and organizers so people can’t envision a different type of life, one where our needs are met and we are not terrorized by the police.”

‘People Have Been Protesting Against Cop City Since We Found Out About It’, FAIR

Vigils For Tortuguita: Land Defenders Erupt In Solidarity, Progressive Hub

Monday, June 12, 2023

Southern Discomfort: Attacks on Freedom Need Condemnation

In North Carolina, Matilda Bliss and Veronica Coit, two reporters from the progressive Asheville Blade, were convicted of “misdemeanor trespassing after being arrested while covering the clearing of a homeless encampment in a public park in 2021.” The judge in the case “said there was no evidence presented to the court that Bliss and Coit were journalists, and that he saw this as a ‘plain and simple trespassing case’” (VoA, 4/19/23).

They’re appealing the conviction (Carolina Public Press, 5/17/23; NC Newsline, 6/2/23), and they have a good bit of support. In April, Eileen O’Reilly, president of the National Press Club, and Gil Klein, president of the National Press Club Journalism Institute, denounced the reporters’ conviction, saying that they “were engaged in routine newsgathering, reporting on the clearing by local police of a homeless encampment” (PRNewswire, 4/20/23). Available evidence, they said, “shows Bliss and Coit did not endanger anyone or obstruct any police activity,” adding that they “were arrested while reporting on a matter of public importance in their community.”

Dozens of other press advocates, including the Committee to Protect Journalists (5/3/23), PEN America (4/25/23) and the Coalition for Women in Journalism (4/19/23), have blasted the convictions.

‘Anti-establishment views’

The house of two of the Atlanta defendants is “emblazoned with anti-police graffiti in an otherwise gentrified neighborhood” (AP, 5/31/23).

In Atlanta, the assault on protesters against “Cop City”—a planned project that would devastate scores of acres of forest land on the city’s south side for a massive military-style security training complex—amped up when Georgia Bureau of Investigation and Atlanta police “arrested three leaders of the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, which has bailed out [anti-Cop City] protesters and helped them find lawyers” (AP, 5/31/23).

The three were charged with money laundering and charity fraud. The “money laundering” consisted of transferring $48,000 from their group, the Network for Strong Communities, to the California-based Siskiyou Mutual Aid—and back again. The “fraud” amounted to the defendants reimbursing themselves for expenses like building materials, yard signs and gasoline. Deputy Attorney General John Fowler seemed to get closer to the actual reason for the prosecution when he said the defendants “harbor extremist anti-government and anti-establishment views” (Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 6/2/23).

When news broke about the arrests, Atlanta activist and journalist circles were abuzz with fears and questions (Atlanta Community Press Collective, 5/31/23). There must be more to the story, right? These people couldn’t simply be arrested for providing bail and legal support—that would be absurd. What next: arresting defense attorneys?

The judge in the case has shared such skepticism, freeing the three on bond despite pressure from the state attorney general not to, and expressing “concerns about their free speech rights and saying he did not find the prosecution’s case, at least for now, ‘real impressive’” (AP, 6/2/23).

Tensions around Cop City are already high. Its projected cost has doubled (Creative Loafing, 5/29/23), dozens of protesters have been hit with domestic terrorism charges (WAGA, 3/5/23) and an autopsy for an activist killed by police “shows their hands were raised when they were killed” (NPR, 3/11/23).

The recent arrests have only raised the temperature. Not long after the three activists were granted bail, the Atlanta City Council “voted 11–4 after a roughly 15-hour long meeting” to approve the project, “sparking cries of ‘Cop City will never be built!’ from the activists who packed City Hall to oppose the measure” (Axios, 6/6/23; Twitter, 6/6/23).

‘Is she real press?’

Slate (6/1/23): “The state’s intention to criminalize dissent could not have been clearer.”

The Atlanta arrests have received considerable press attention. Slate (6/1/23) and the Intercept (5/31/23) wrote pieces highlighting the severity of the charges. The Asheville case, despite considerable outcry from press advocates, hasn’t had much attention outside left-wing and local press, with the surprising exception of a report on Voice of America (4/19/23), a US government–owned network.

What neither of these cases has received is an outcry from major newspaper editorial boards or network news shows, calling attention to their violation of constitutional rights—although the Atlanta arrests did get a news story in the New York Times (6/2/23) that included condemnations from civil liberties groups. (MSNBC published an op-ed denouncing the arrests on its website—6/3/23.) At FAIR, I have rung the alarm that journalists for both mainstream and small outlets have faced arrests (3/16/21) and extreme police violence (9/3/21). These incidents are part of that trend.

In the Asheville instance, Judge James Calvin Hill was already hostile toward the reporters’ First Amendment claims, as he questioned whether they were actually journalists (Truthout, 6/1/23). “She says she’s press,” a police officer said in court of Coit, to which Hill responded: “Is she real press?”

The Asheville Blade is a small, scruffy left-wing outlet; are we to assume that courts will determine what constitutes a journalistic outlet based on budget, size of distribution, popularity and political orientation?

In the case of the Atlanta arrests, coverage often carried photos of the activists’ Eastside house, painted purple with anti-police signage and graffiti. This hippie vibe might not be the image Atlanta’s powerful business class wants to project as the commercial center of the South; the Atlanta Police Foundation includes support from some of the city’s top corporations (New Yorker, 8/3/23), including Coca-Cola, Delta, Home Depot—and Cox, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution‘s parent company.

The Journal-Constitution, the major local paper, has run pieces (5/8/21, 1/25/23, 3/8/23) in favor of Cop City and other aggressive anti-crime tactics. Its editorial board (8/21/21) declared, “There’s no time to waste in moving to replace the city’s current, dilapidated training grounds,” because “criminals will continue to ply their trade, exacting a cost in property, public fears and even lives.”

Needless to say, this is not the way the Asheville Blade writes about police issues. But that shouldn’t matter, because constitutional rights, by their definition, are not supposed to discriminate.

Concern for freedom—elsewhere

The New York Times‘ concern (6/5/23) for a persecuted journalist is not so rare—at least when the persecutors are official enemies.

We live in a media environment (FAIR.org, 10/23/20, 11/17/21, 3/25/22) where we must constantly endure think piece after think piece about whether conservative college students are safe from ridicule if they come out against nonbinary pronouns, or if a comedian has suffered a dip in popularity because their schtick is considered “unwoke.” Governments actually trying to imprison people for exercising their constitutional rights somehow don’t generate the same sense of alarm in establishment media.

Unless, of course, those governments are abroad, in official enemy nations. The New York Times (6/5/23) prominently reported a “rare victory for journalism amid a crackdown on the news media in Hong Kong” after a court “overturned the conviction of a prominent reporter who had produced a documentary that was critical of the police.” When Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich was arrested in Russia, this was naturally covered, not just by his own paper (3/31/23) but its rivals as well (New York Times, 5/23/23; Washington Post, 5/31/23).

If our media really cared about the future of free discourse in contemporary America, and the state of freedom of speech and association, Atlanta and Asheville would be the focus of the same sort of media attention.

‘People Have Been Protesting Against Cop City Since We Found Out About It’, FAIR

Vigils For Tortuguita: Land Defenders Erupt In Solidarity, Progressive Hub

Thursday, July 14, 2022

Not One Single Republican Votes for Probe of Neo-Nazis in US Military and Police

|

| photo credit:Anthony Crider |

Rep. Brad Schneider's (D-Ill.) amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for fiscal year 2023 directing the FBI, Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Defense "to publish a report that analyzes and sets out strategies to combat white supremacist and neo-Nazi activity in the uniformed services and federal law enforcement agencies" passed in a party-line 218-208 vote.

Thursday, June 30, 2022

Flint Residents 'Disgusted' After Court Throws Out Indictments of Top Officials

"This leaves no one criminally responsible for poisoning 100,000 people in one of the largest public health disasters in this nation's history," Flint Rising said in a statement Wednesday, adding that the group is "disgusted" by the 6-0 decision.

"It has been 2,986 days since the start of the Flint water crisis. Throughout the years, we've sent buses of Flint residents to our state and nation's capital, shared our stories, marched in the streets, and fought for reparations for our community," the group continued.

Thursday, May 26, 2022

Press Makes Trump, Not Voting Rights, the Primary Issue

The Washington Post (5/24/22) reported that Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp’s GOP primary win “threatened Trump’s reputation as GOP kingmaker.”

The country’s centrist corporate media have decided what this year’s primaries are mainly about: Donald Trump.

In the wake of an attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election and continued efforts by the Republican Party to undermine democratic processes, corporate media remain fixated on Trump’s role in the party, seeing the 2022 primaries as a series of referenda on Trump and his role as kingmaker. But the focus on Trump obscures the even more important story that Trump represents: the GOP assault on democracy, which is being carried out only marginally less aggressively by many of those “defeating” him.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp is the perfect example of this. After this week’s state primaries, most corporate media made their lead story the losses of Trump-backed candidates, in particular to Kemp and Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, who both played very public roles in refusing to bow to Trump’s demands to “find” votes for him in Georgia in 2020.

The Washington Post (5/24/22) declared, “Kemp, Raffensperger Win in Blow to Trump and His False Election Claims.” A New York Times (5/24/22) subhead read, “The victories in Georgia by Gov. Brian Kemp and Brad Raffensperger, the secretary of state, handed the former president his biggest primary season setback so far.” At Reuters (5/24/22), the top “takeaway” subhead read: “Trump Takes Lumps.”

These are stories centrist media like to tell: The voters are sensibly rejecting extremists from their party, so the “moderate” candidates are taking the right path. Journalists tell this story over and over in coverage of Democratic primaries, with “move to the center” stories encouraging the party to reject its progressive candidates. The problem is, candidates like Kemp and Raffensperger are not moderate, except in comparison to Trump—and painting the story as one centrally about Trump obscures the anti-democratic nature of those who defeated his hand-picked candidates.

The Boston Globe (5/24/22) noted that “Kemp had not beaten back the 2020 doubts of voters [who thought that election “stolen”]; he simply found a different way to champion them than Trump.”

The Globe‘s Jess Bidgood reported:

Kemp’s easy win over Perdue on Tuesday may seem to suggest that the former president and his baseless insistence that fraud and irregularities cost him the election have lost their iron grip on the Republican Party….

Even though he stood up to Trump’s attempts to overturn the 2020 election, Kemp found other ways to assuage the GOP base’s unfounded doubts about the issue. He signed a voting bill that added new hurdles to absentee voting and handed some election oversight power over to the Republican-controlled legislature. He spoke of “election integrity” everywhere he went, while Raffensperger leaned into the issue as well.

But even this didn’t go nearly far enough in describing Kemp and Raffensperger’s histories of attacking voting rights. As Georgia’s secretary of state, Kemp for years vigorously promoted false election fraud stories and made Georgia a hotspot for undermining voting rights. He aggressively investigated groups that helped register voters of color; in 2014, he launched a criminal investigation into Stacey Abrams’ New Georgia Project—which was helping to register tens of thousands of Black Georgians who previously hadn’t voted—calling their activities “voter fraud.” His investigation ultimately uncovered no wrongdoing (New Republic, 5/5/15).

Kemp oversaw the rejection of tens of thousands of voter registrations on technicalities like missing accents or typos (Atlantic, 11/7/18) and improperly purged hundreds of thousands of voters from the rolls prior to the 2018 election (Rolling Stone, 10/27/18), disproportionately impacting voters of color (Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 3/12/20). He refused to recuse himself from overseeing his own race for governor against Abrams, drawing rebukes from former president, Georgia native and fair elections advocate Jimmy Carter (The Nation, 10/29/18), among others. Kemp ran that governor’s race as a “Trump conservative.”

None of Kemp’s history as anti–voting rights secretary of state was mentioned in any of the next-day election coverage FAIR surveyed. (There was an opinion piece on CNN.com on May 26 that detailed “Kemp’s appalling anti-democracy conduct.”)

As governor, Kemp has further eroded voting rights in Georgia, as mentioned by the Globe (a story that the media managed to both-sides at the time—FAIR.org, 4/8/21). He has also taken a hard-right stance on many other rights issues, signing into law a bill to prohibit “divisive concepts” from being taught in schools, a bill to ban abortions as early as six weeks and a bill discriminating against transgender kids in sports.

Like Kemp, Raffensperger was an early supporter of Trump who pushed election fraud stories and voter suppression tactics. As FAIR (3/5/21) pointed out at the time, centrist media fawned over Raffensperger for standing up to Trump in the 2020 election, ignoring his “support of the little lies that made the Big Lie possible.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (1/4/21) editorialized that Georgia Secretary of State Brad “Raffensperger deserves kudos from all Georgians for continuing a principled stand for what is right,” weeks after reporting (12/17/20) that “the secretary has helped fuel suspicions about the integrity of Georgia’s elections.”

For instance, just weeks before an uncritical editorial (1/4/21) praising him, the local Journal-Constitution published a front-page investigation (12/17/20) that found Raffensperger was touting “inflated figures about the number of investigations his office was conducting related to the election, giving those seeking to sow doubt in the outcome a new storyline.” Those claims helped propel the state’s 2020 bill restricting voting rights.

Like Kemp, he launched vote fraud investigations into progressive voter registration groups (AJC, 11/30/20), and oversaw the purge of nearly 200,000 voters, mostly people of color, from the rolls before the 2020 election (Democracy Now!, 1/5/21).

During his re-election campaign, Raffensperger had gone on national television (CBS, 1/9/22) to push for a constitutional amendment prohibiting noncitizens from voting in any elections, as well as to praise photo ID requirements for voting and oppose same-day voter registration. He has also called for an expansion of law enforcement presence at polling sites.

In their obsession with Trump’s win/loss record and their desperate search for “moderate” Republicans, journalists whitewash GOP candidates who paved the way for Trumpism and, ultimately, seek the same end—minority rule—by only slightly different means.

Featured image: Reuters (5/24/22) depiction of Donald Trump illustrating the takeaway, “Trump Takes Lumps.”

Reprinted with permission from FAIR.org. FAIR’s work is sustained by our generous contributors, who allow us to remain independent. Donate today to be a part of this important mission.

Tuesday, May 17, 2022

Abortion has been common in the US since the 18th century – and debate over it started soon after

State-by-state battles are heating up in the wake of news that the U.S. Supreme Court appears poised to overrule landmark rulings - Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey - and remove constitutional protection for the right to get an abortion.

Now, pro- and anti-abortion advocates are gearing up for a new phase of the abortion conflict.

While many people may think that the political arguments over abortion now are fresh and new, scholars of women’s, medical and legal history note that this debate has a long history in the U.S.

It began more than a century before Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that established that the Constitution protects a person’s right to an abortion.

The era of ‘The Pill’

On Nov. 14, 1972, a controversial two-part episode of the groundbreaking television show, “Maude” aired.

Titled “Maude’s Dilemma,” the episodes chronicled the decision by the main character to have an abortion.

Roe v. Wade was issued two months after these episodes. The ruling affirmed the right to have an abortion during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. “Maude’s Dilemma” brought the battle over abortion from the streets and courthouses to primetime television.

Responses to the episodes ranged from celebration to fury, which mirrored contemporary attitudes about abortion.

Less than 10 years before “Maude’s Dilemma” aired, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first commercially produced birth control pill, Enovid-10.

Although various forms of birth control predate the birth control pill, the FDA’s approval of Enovid-10 was a watershed in the national debate around family planning and reproductive choice.

Commonly known as “The Pill,” the wider accessibility of birth control is seen as an early victory of the nascent women’s liberation movement.

Abortion also emerged as a prominent issue within this burgeoning movement. For many feminist activists of the 1960s and 1970s, women’s right to control their own reproductive lives became inextricable from the larger platform of gender equality.

From unregulated to criminalized

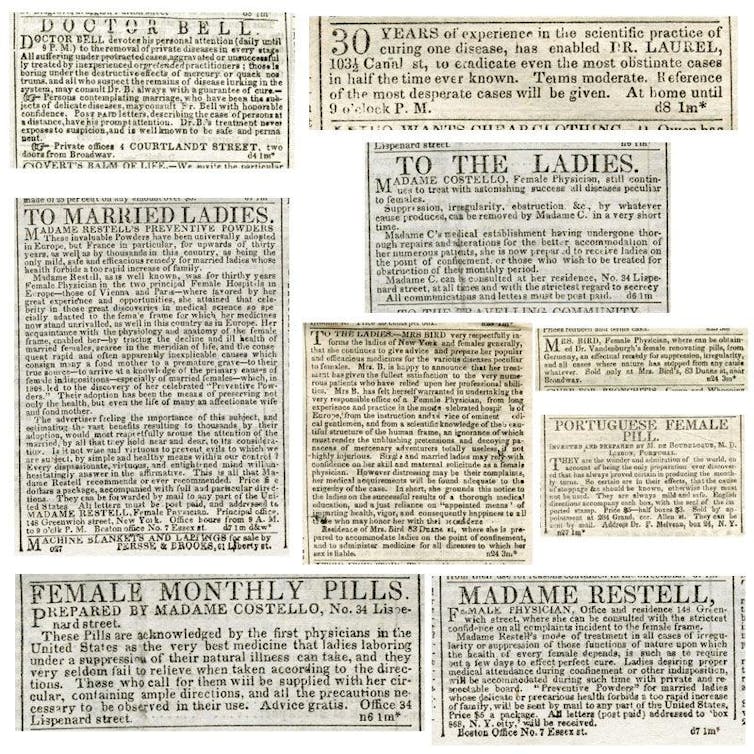

From the nation’s founding through the early 1800s, pre-quickening abortions – that is, abortions before a pregnant person feels fetal movement – were fairly common and even advertised.

Women from various backgrounds sought to end unwanted pregnancies before and during this period both in the U.S. and across the world. For example, enslaved black women in the U.S. developed abortifacients – drugs that induce abortions – and abortion practices as means to stop pregnancies after rapes by, and coerced sexual encounters with, white male slave owners.

In the mid- to late-1800s, an increasing number of states passed anti-abortion laws sparked by both moral and safety concerns. Primarily motivated by fears about high risks for injury or death, medical practitioners in particular led the charge for anti-abortion laws during this era.

By 1860, the American Medical Association sought to end legal abortion. The Comstock Law of 1873 criminalized attaining, producing or publishing information about contraception, sexually transmitted infections and diseases, and how to procure an abortion.

A spike in fears about new immigrants and newly emancipated black people reproducing at higher rates than the white population also prompted more opposition to legal abortion.

There’s an ongoing dispute about whether famous women’s activists of the 1800s such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony opposed abortion.

The anti-abortion movement references statements made by Anthony that appear to denounce abortion. Abortion rights advocates reject this understanding of Stanton, Anthony and other early American women’s rights activists’ views on abortion. They assert that statements about infanticide and motherhood have been misrepresented and inaccurately attributed to these activists.

These differing historical interpretations offer two distinct framings for both historical and contemporary abortion and anti-abortion activism.

Abortion in the sixties

|

| Photo credit: SHYCITY nikon |

By the turn of the 20th century, every state classified abortion as a felony, with some states including limited exceptions for medical emergencies and cases of rape and incest.

Despite the criminalization, by the 1930s, physicians performed almost a million abortions every year. This figure doesn’t account for abortions performed by non-medical practitioners or through undocumented channels and methods.

Nevertheless, abortion didn’t become a hotly contested political issue until the women’s liberation movement and the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. These movements brought renewed interest in public discussions about reproductive rights, family planning and access to legal and safe abortion services.

In 1962, the story of Sherri Finkbine, the local Phoenix, Arizona host of the children’s program, “Romper Room,” became national news.

Finkbine had four children, and had taken a drug, thalidomide, before she realized she was pregnant with her fifth child. Worried that the drug could cause severe birth defects, she tried to get an abortion in her home state, Arizona, but could not. She then traveled to Sweden for a legal abortion. Finkbine’s story is credited with helping to shift public opinion on abortion and was central to a growing, national call for abortion reform laws.

Two years after Finkbine’s story made headlines, the death of Gerri Santoro, a woman who died seeking an illegal abortion in Connecticut, ignited a renewed fervor among those seeking to legalize abortion.

Santoro’s death, along with many other reported deaths and injuries also sparked the founding of underground networks such as The Jane Collective to offer abortion services to those seeking to end pregnancies.

Expanding legal abortion

In 1967, Colorado became the first state to legalize abortion in cases of rape, incest, or if the pregnancy would cause permanent physical disability to the birth parent.

By the time “Maude’s Dilemma” aired, abortion was legal under specific circumstances in 20 states. A rapid growth in the number of pro- and anti-abortion organizations occurred in the 1960s and 1970s.

On Jan. 22, 1973, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Roe v. Wade nullified existing state laws that banned abortions and provided guidelines for abortion availability based upon trimesters and fetal viability. The subsequent 1992 ruling known as Casey reaffirmed Roe, while also allowing states to impose certain limits on the right to abortion. Roe remains the most important legal statute for abortion access in modern U.S. history.

Since Roe, the legal battle over abortion has raged, focused on the Supreme Court. If the draft opinion overruling Roe and Casey stands, the battle will end there and shift to the states, which will have the power to ban abortion without fear of running afoul of the Supreme Court. And the long history of conflict over abortion in the U.S. suggests that this will not be the last chapter in the political struggle over legal abortion.

This story is an updated version of an article published on June 10, 2019.![]()

Treva B. Lindsey, Professor of Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies, The Ohio State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

.jpeg)