Left out of GOP debates about “the weaponization” of the federal government is the use of the FBI to spy on civil rights leaders for most of the 20th century.

Martin Luther King Jr. was one of the targets.

As secret FBI documents became declassified, The Conversation U.S. published several articles looking at the details that emerged about King’s personal life and how he was considered in 1963 by the FBI as “the most dangerous Negro.”

1. The radicalism of MLK

As a historian of religion and civil rights, University of Colorado Colorado Springs Professor Paul Harvey writes that while King has come to be revered as a hero who led a nonviolent struggle to build a color blind society, the true radicalism of MLK’s beliefs remain underappreciated.

“The civil saint portrayed nowadays was,” Harvey writes, “by the end of his life, a social and economic radical, who argued forcefully for the necessity of economic justice in the pursuit of racial equality.”

2. The threat of being called a communist

Jason Miller, a North Carolina State University English professor, details the delicate balance that King was forced to strike between some of his radical allies and the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

As the leading figure in the civil rights movement, Miller explains, King could not be perceived as a communist in order to maintain his national popularity.

As a result, King did not overtly invoke the name of one of the Harlem Renaissance’s leading poets, Langston Hughes, a man the FBI suspected of being a communist sympathizer.

But Miller’s research reveals the shrewdness with which King still managed to use Hughes’ poetry in his speeches and sermons, most notably in King’s “I Have a Dream” speech which echoes Hughes’ poem “I Dream a World.”

“By channeling Hughes’ voice, King was able to elevate the subversive words of a poet that the powerful thought they had silenced,” Miller writes.

3. ‘We must mark him now’

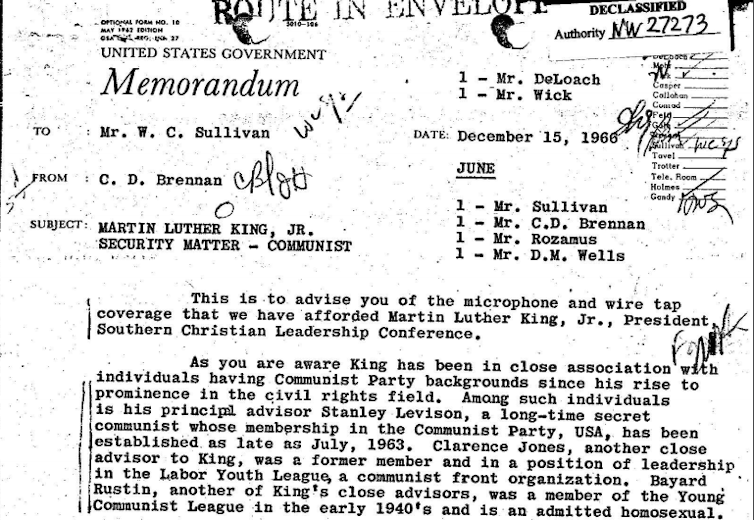

As a historian who has done substantial research regarding FBI files on the Black freedom movement, UCLA labor studies lecturer Trevor Griffey points out that from 1910 to the 1970s, the FBI treated civil rights activists as either disloyal “subversives” or “dupes” of foreign agents.

As King ascended in prominence in the late 1950s and 1960s, it was inevitable that the FBI would investigate him.

In fact, two days after King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, William Sullivan, the FBI’s director of intelligence, wrote: “We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro and national security.”

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.![]()

Howard Manly, Race + Equity Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment