Behind the walls, Jackson organized the prisoners and became a leader of the Black prison movement in San Quentin. His role there enabled his unique installation as the Field Marshal in the Black Panther Party’s Central Committee. It is Jackson’s political and radical transformation that brings our attention to the state’s response to his prison activism.

His organizing activities were criminalized to justify COINTELPRO activities that viewed Jackson as a target for state violence. Just as radical Black political activism was deemed a threat and criminalized outside the prison walls, George Jackson pointed us to the criminalization of organizing activities behind the prison walls.

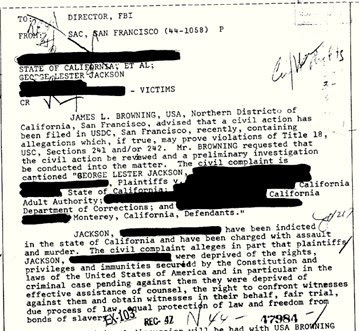

COINTELPRO not only enabled the murder of George Jackson but the increasingly number of political prisoners being incarcerated behind the walls as well. The FBI’s counterintelligence program commonly known as COINTELPRO, was in operation from 1956 to 1971: “The purpose of this new counterintelligence endeavor is to expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, and otherwise neutralize the activities of black nationalist organizations and groupings and their leadership, spokesmen, membership, and supporters.”

Because of COINTELPRO, organizational financial resources were depleted due to the repeated arrests and convictions based on fabricated or withheld evidence. There was also the murder, exile and incarceration of political prisoners who languished behind the walls for over 20, 30, 40 and yes, 50 years. Political prisoners were created by the state’s response of state repression, violence and incarceration to their political positions and actions of the late sixties and early seventies. As activists and organizers, they exercised a relentless pursuit of self-determination with a clear analysis of their current political, economic and social condition. They were committed to transforming an American apartheid society with their political activism and organizing. As a result, their political activities were criminalized and were subsequently rendered, enemies of the state.

Fifty years later, their status as political prisoners are denied by the government. Instead, they’re branded as criminals and/or domestic terrorists while disregarding COINTELPRO’s illegal activities that secured their incarceration. Not only is their existence in denial by the United States government but on a broader level, there’s also the denial of human rights abuses on US soil and their disregard for certain international laws and treaties around human rights and political prisoners.

Although, COINTELPRO officially disbanded operations in 1971, political surveillance continued under apparent ongoing COINTELPRO-like activities. For instance, there’s the historic Handshu case on NYPD’s surveillance and intelligence-gathering activities on political groups as well as the revelations of a NYPD police unit, known as the Black Desk, assigned to surveilling Black radical organizations.

These COINTELPRO-like activities continued with targeting former political prisoners, such as ImamBut more recently, an early dawn FBI raid on the African People’s Socialist Party has been denounced widely by activists and organizations who quickly recognized the COINTELPRO-like pattern here. The African People’s Socialist Party is known for their extensive work in the Black community in St. Louis, and international work. They’ve been branded as pawns of the Russian government in the ongoing global game of chess, under the hollow pretext they were involved in Russia’s influence and role in undermining American elections.

This early morning raid was conducted on the very same premise afforded only for those on the forefront of struggle for Black liberation. Black August reminds us, the FBI raid is yet another example of targeted Black folk who are under far more intense political surveillance for their constitutionally protected advocacy of exercising self-determination and black liberation. During Black August, we’re not only reminded of political prisoners, and their sacrifice but we’re also reminded of why they’re political prisoners. Most importantly, Black August presents another opportunity to amplify the fight to release political prisoners as central any movement advocating for human rights and anti-racism.